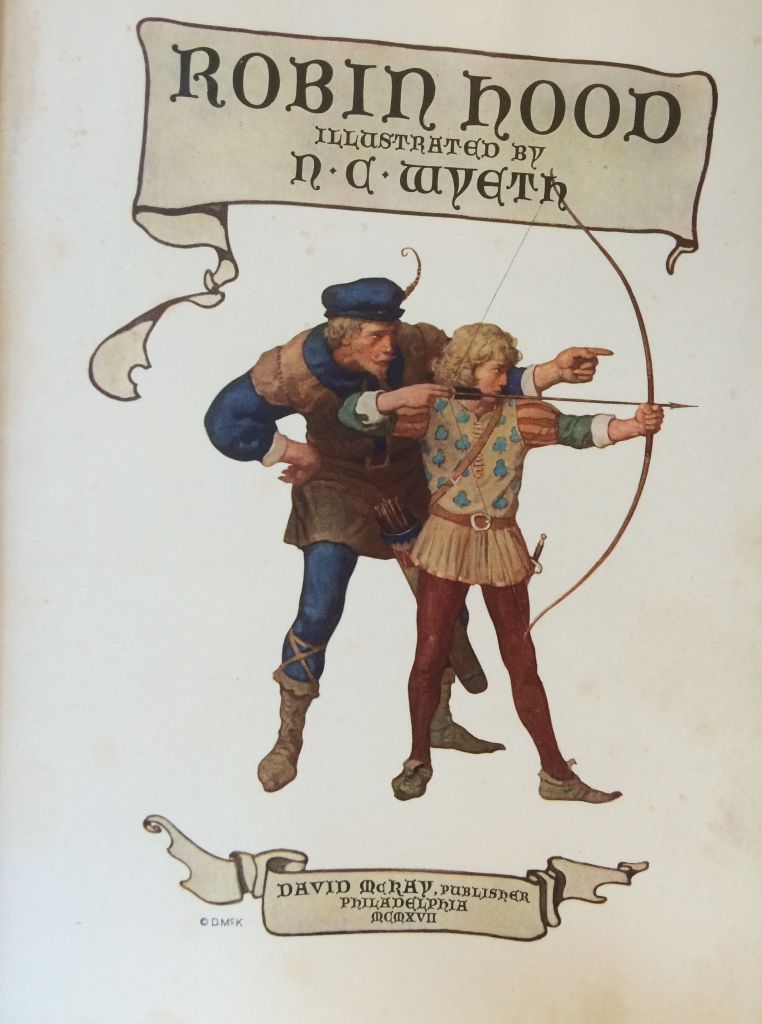

Andrew Wyeth, born in 1917 to artist N.C. Wyeth and mother Carolyn was the youngest of 5 children. Before he even learned to hold a brush, his parent’s expectations for him were as high as for the rest of his siblings. His sisters Henriette and Carolyn were already proving themselves to be accomplished in paints, his third sister Ann accomplished in music, and his brother Nathanial, perhaps an odd-duck in the family of artists, had a penchant for the sciences and went on to invent one of our most important composite plastics still in use today, polyethylene terephthalate (PET). As young Andrew was learning to walk, to speak, to understand his place in the world, he came to discover that his place had already been prepared in the minds of his parents. He was kept home on account of poor health, now believed to be undiagnosed tuberculosis, and tutored by his father, a successful and well-known illustrator of children’s books, such as Treasure Island and Robin Hood. As Andrew grew older, he reflected on this time with some criticism of his father as a teacher, “Pa kept me almost in a jail, he just kept me to himself in my own world, and he wouldn’t let anyone in on it. I was almost made to stay in Sherwood Forest with Maid Marion and the rebels”. Little Andrew would watch his brother and sisters leave for school in the mornings and spend his days with his parents, insulated from the rest of the world. Unable to fully investigate his childhood curiosities and forced into premature adulthood, Andrew would grow up to paint the only world he ever knew: the stark, cold, and lonely landscapes of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

Into his teens, Andrew worked as an illustrator under his father’s name, and then eventually under his own name. He eventually began pursuing his own interests, experimenting with watercolor and impressionism and creating a small body of work that he would exhibit in New York for his first show. Despite being only 20 years old, the show was an ultimate success resulting in the sale of every piece. As his career continued, he eventually found his voice in more defined depictions of the rural spaces around his home. Empty landscapes with sun bleached color was a popular motif for Wyeth, though scenes were overcast devoid of defined shadow, hiding away the sun that had caused the weathering of the subjects. It was as though he lived in a world where the sun never rose nor set, but was locked in a thick blanket of clouds for all time. And if his scenes included a human figure, which was rare, that person was always alone in dark contrasts of muted color. His favorite subject matter is what gave Wyeth his standing as a regionalist painter. Like other artists of the time Grant Wood and Thomas Benton, he was fond of depicting scenes that were uniquely American- as if his images were love letters to Americana itself.

Essential to his mission of painting the world around him was his use of egg tempura as a medium. This challenging technique of mixing ground pigments with egg yolk was taught to him by his brother-in-law and provided him the ability to capture fine detail on his canvas in deeply saturated pigments. As this ability was developed over time, critics of his work attempted to label him as a realist painter- as one who attempts to recreate a scene as faithfully as a photograph. Wyeth disagreed with this categorization, taking offense that his critical eye could be no different than the mechanical operation of a glass lens attached to a box. Thoughtful examination of his work shows just how different his perspective was from a camera that simply reproduces an image using chemistry and is subject to the laws of physics.

Take for instance, his painting titled “Winter Fields” (1942). On a walk near his home, Wyeth found a crow frozen in a field and brought it home to paint in exquisite detail. He paints the crow in the foreground of a sweeping hillside of dormant prairie grass and harvested grain sheaves. In the far distance is a farmhouse and barn, some craggy leafless trees, and the suggestion of a forest line. The scene looks almost like a photograph, but he paints the bird in a perspective that brings the viewer’s eye to ground level. This perspective is completely unnatural, as a person would need to be standing in a hole to achieve this vantage point. Wyeth is depicting the cold inevitability of death, and has his viewer standing in the ground that this crow, and all of us, will eventually return to as dust.

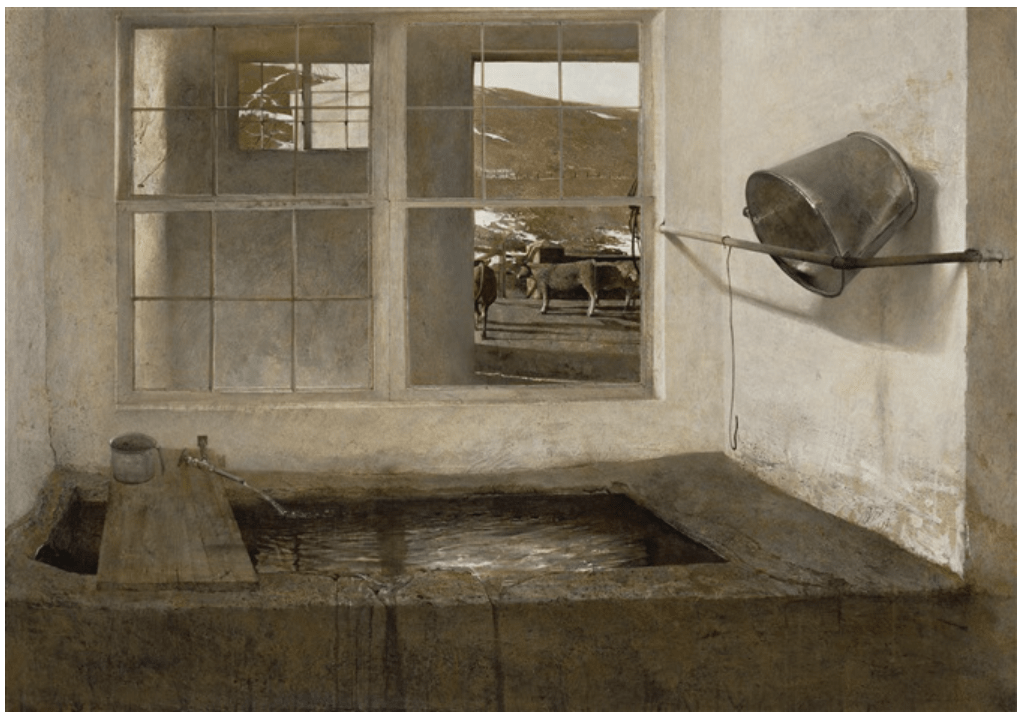

Another example of his twist on reality is in his highly detailed work titled “Spring Fed” (1967). Unlike a photograph that will always have regions outside of the focal plane due to limitations of light and optics, Wyeth carries sharp detail from the stone sink in the foreground to the grazing cows in the far depth of the scene. This allows us as a viewer to exchange focus on the foreground and background at will, as we would experience a scene in real life, without having our views framed or forced into a narrow perspective. But Wyeth does frame a view for us, as an open doorway shows us cows standing in the distance. The cows aren’t grazing; the grass around them is brown, and there are ribbons of snow in the hillside beyond. It is winter once more in Wyeth’s world, and we can’t help but wonder why the cows aren’t in hunkered down in the barn for the winter. The cows are looking off at something we can’t see; perhaps they are being sold and sent off to another farm. Perhaps they are being purchased and sent to slaughter. We turn our attention away, further studying the detail of a shiny bucket propped near the stone sink. One can’t help but to squint at the reflections in the bucket to see if a glimpse of the artist can be caught. Alas, none can be found, reminding us that this not a depiction of reality but instead a story that Wyeth is weaving together for the viewer.

Wyeth was an incredibly successful painter in his long career from drafting and illustrations with his father till his death in 2009. Critics either raved for his work that broke the mold of realism or lambasted him for failing to fully commit to any particular school of art- he wasn’t realist enough, or modern enough, or abstract enough for their taste. This serves as a reminder that regardless of what era we inhabit, some people speak just to hear the sound of their own voices reverberating through their lonely halls. Their clever opinions are merely the splatter of paint left behind on an easel once the artist has finished their work and taken it away to share with the world.

Potter, Polyxeni. “On the Threshold of Illness and Emotional Isolation.” Emerging Infectious Diseases vol. 12,5 (2006): 878–879. doi:10.3201/eid1205.AC1205

Kimmelman, Michael. “Andrew Wyeth, Painter, Dies at 91” The New York Times, January 16, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/17/arts/design/17wyeth.html

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Andrew Wyeth”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 Apr. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Wyeth. Accessed 23 April 2024.

Wikipedia, contributing authors. “Andrew Wyeth”. Wikipedia, 7 Apr. 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Wyeth

Leave a comment